Hello world. Welcome to the April 2025 edition of my Universal Sandpit Quarterly.

There is so much to share with you. It has been a busy and fruitful beginning to the year. I hope you find something of value in my lead essay on AI, creativity and mastery - it speaks to a domain of education and technology that’s been occupying much of my thinking lately. That essay is called ‘Long Legs and Mountain Peaks’ and is just beneath this introduction.

It is followed by a secondary essay on neurodiversity and neurodivergence, exploring a territory I have called ‘Neuroalethia’. See what you think :)

Briefly, I’ll share a few things I’ve been involved in that you might like to explore further, as part of this edition of my journal -

I created a neat little workflow whereby Apple Maps and ChatGPT talk to each other, for the purpose of conducting sensory and environmental audits on locations you might take a class of students to. You can watch a video demo here:

I spoke to ABC Radio about my TEDx talk on walking and talking with AI, which you can listen to here:

And, on a creative front, I published a piece of theatre for the stage that I call ‘Ambient 1-4’, a composition I wrote for an Aphex Twin tribute album was released, and I wrote and performed a song in eight hours at the Maitland Art Gallery as part of a terrific day called ‘8 to Create’, which you can watch here:

I have also had some great podcast conversations with folks from around the world, including this one with Ben Woodrow-Hirst at The University of Staffordshire, which was a lot of fun. We go into some pretty wild territory regarding AI, Augmented Reality and more:

That’s enough for now - there have been lots of other interesting experiences that I want to share with you, but I’ll save those for the next edition of this journal. Otherwise, I’ll never get to what I really want to say.

Let’s begin.

Long Legs and Mountain Peaks

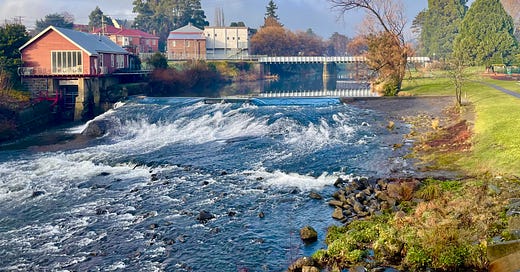

I’ve just returned from a work trip to Tasmania. I was briefly there collaborating with colleagues on autism education workshops. As always, even when the topic is not AI, certain dialogues quickly turn in that direction.

Let me share a story I told there. My son is five and is learning to draw (my daughter is fifteen and is a terrific artist, just like her mother). He is also learning to tell stories, to play music, to dance… because he’s five, and he wants to do everything, fuelled by his infinite energy and zest for life. My son and I use technology for all sorts of creative activities - we make movies together, we apply filters and special effects to our movies, we write soundtracks, we use special effects to modulate our voices. And, now and again, we use AI.

I took my son to a trampoline park the other day and he wanted me to film him and make the footage look like he was in a Minecraft world (using Sora).

Of course, let’s do it:

Then, on a rainy Sunday, we made a Minecraft-themed comic by taking photos around the house. My son posed, set up props, and then sat with me while we rendered our photos in a blocky way. Now, we read the comic and others we have made every day. You can read the Minecraft-themed comic here:

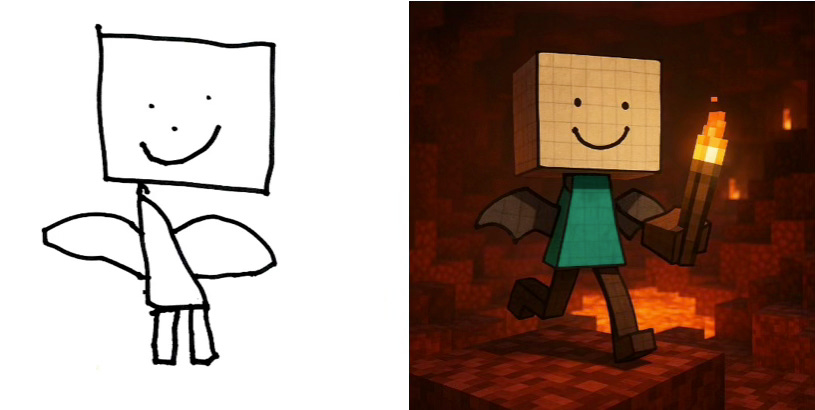

Now here is where things get interesting. My son drew a picture of a character that he wanted to think about for a Minecraft story he was writing. He sketched his version on paper and then asked me to turn it something that looked like it was actually in Minecraft. So, we photographed it, put it into Sora, and got the following:

He loved it, looked at it for a while, and then began working on a story about the character, telling me all the things the character would do, and then we acted out the scenes, played games, and so on.

The big ethical question here, and the pedagogical situation attached, is “will my son be less inclined to practice drawing, and develop into an artist of quality, if he can just get the magic machine to be an artist for him?”

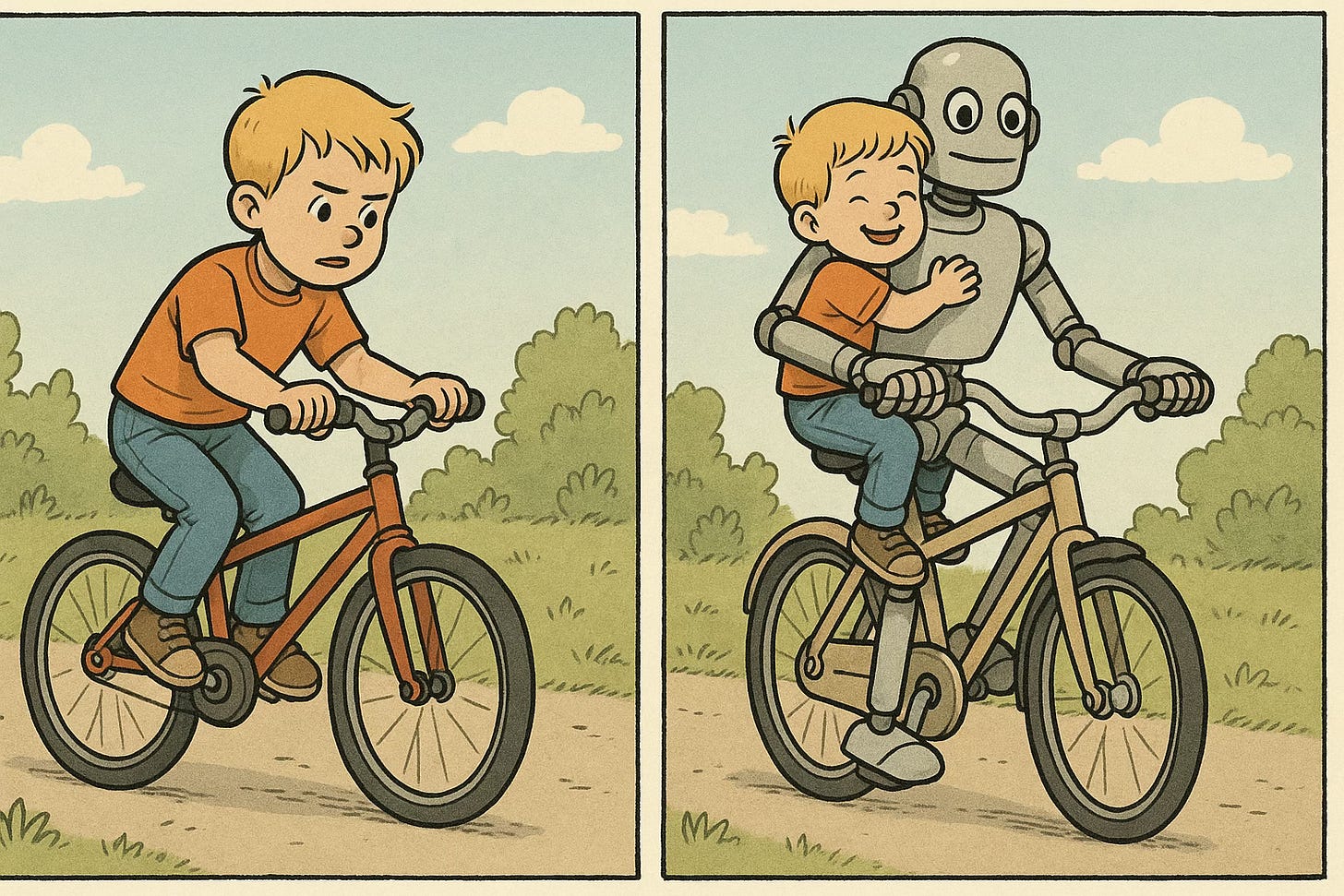

I’ve been working with pre-service teachers at a university recently on ‘digital literacy in the age of AI’, and one of the central metaphors we return to is the Steve Jobs line about technology being a bicycle for the mind. So the idea goes, technology can, when used in certain ways, act as a tool to help the mind travel further, with more speed and efficiency, than if it were travelling on its own accord.

That’s a fine and useful sentiment. Riding a bike is a good action to interrogate, because it’s a rite of passage for many young people to master: you try, you fall, you get up again, you try again, fall again, and keep on until you get the balance and the momentum just right. And then, you feel amazing because you’re riding a bike.

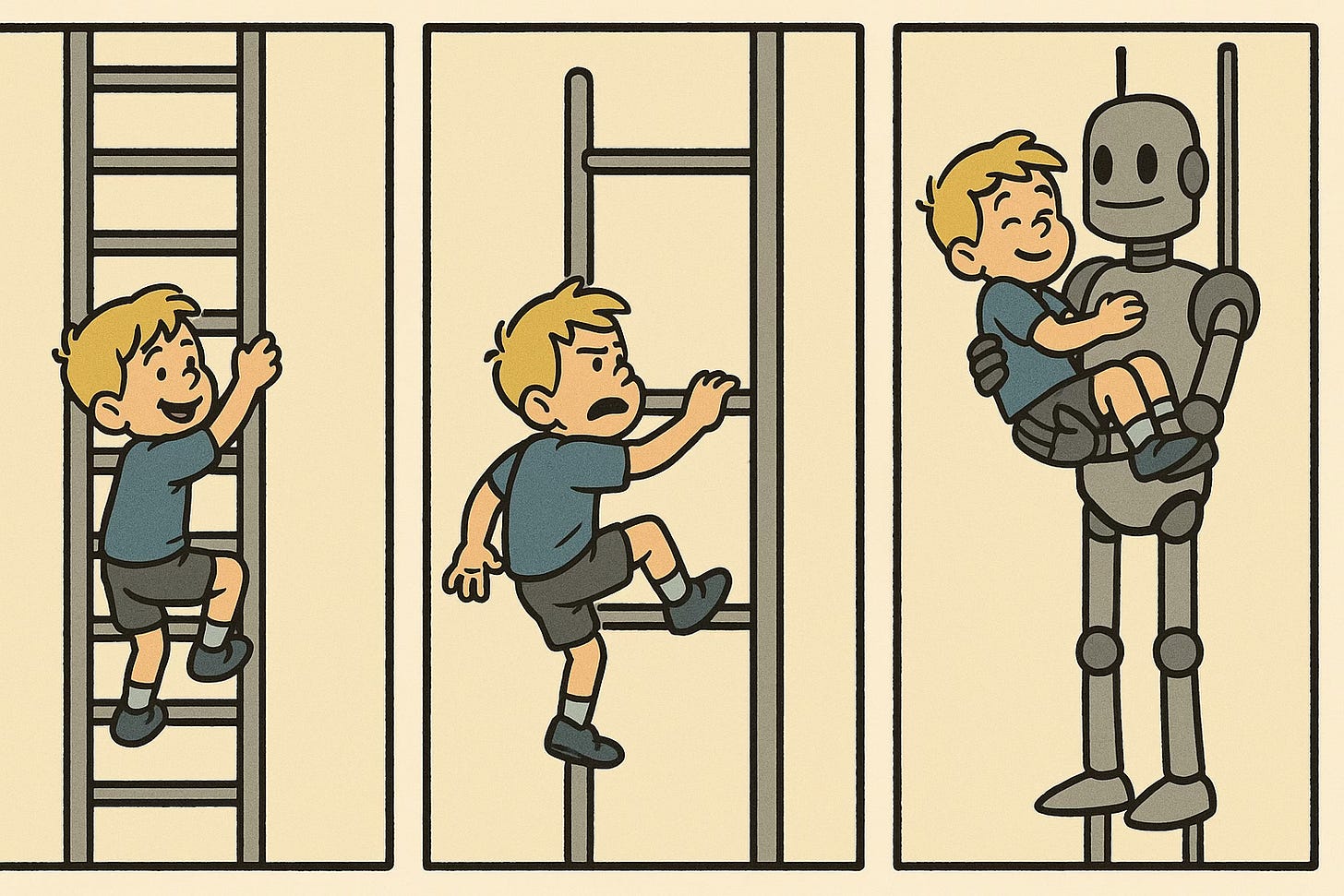

What technology can do, sometimes very purposefully, is take away ‘the fall’. Some years ago an internet dating agency came out with a platform that promised to take away the ‘fall’ from ‘falling in love’ - the idea was, take away the risk, the struggle, and just yield the benefits, the ‘love’ without the ‘fall’. I asked AI to create a comic that showed this dynamics with bike riding - a boy (who looks remarkably similar to my son) learning to ride a bike, and then a boy being carried by a robot who is riding the bike for him:

Is this the situation I’m setting up for my son, with his budding interest in drawing? If he has an image in his head, but his own illustration doesn’t yet match up, and so he uses AI to bring the image in his head into a form he can see in front of his eyes, without having to draw it, will he ever try hard to learn to draw for himself? Or, as in the comic above, will the robot do it for him - ride the bike, carrying him along, saving ‘the fall’, the struggle of overcoming and achieving?

(Let alone, of course, the concerns about the AI simply creating a highly generalised, crowd-sourced/stolen version of art, etc - that’s another discussion).

But there is another perspective here, too. My son went on to create a story after the AI version of his artwork was produced. He turned it into a whole narrative that built and evolved into the acting out of scenes, role-play, games, and all the rest. He would look back at the AI-generated artwork and get a new burst of inspiration.

What if the AI-generated artwork was the creative catalyst for his true passion, telling a story? In this case, his illustration was a starting point, and the AI-rendered version brought it to life to achieve his actual goal - fuel for narrative.

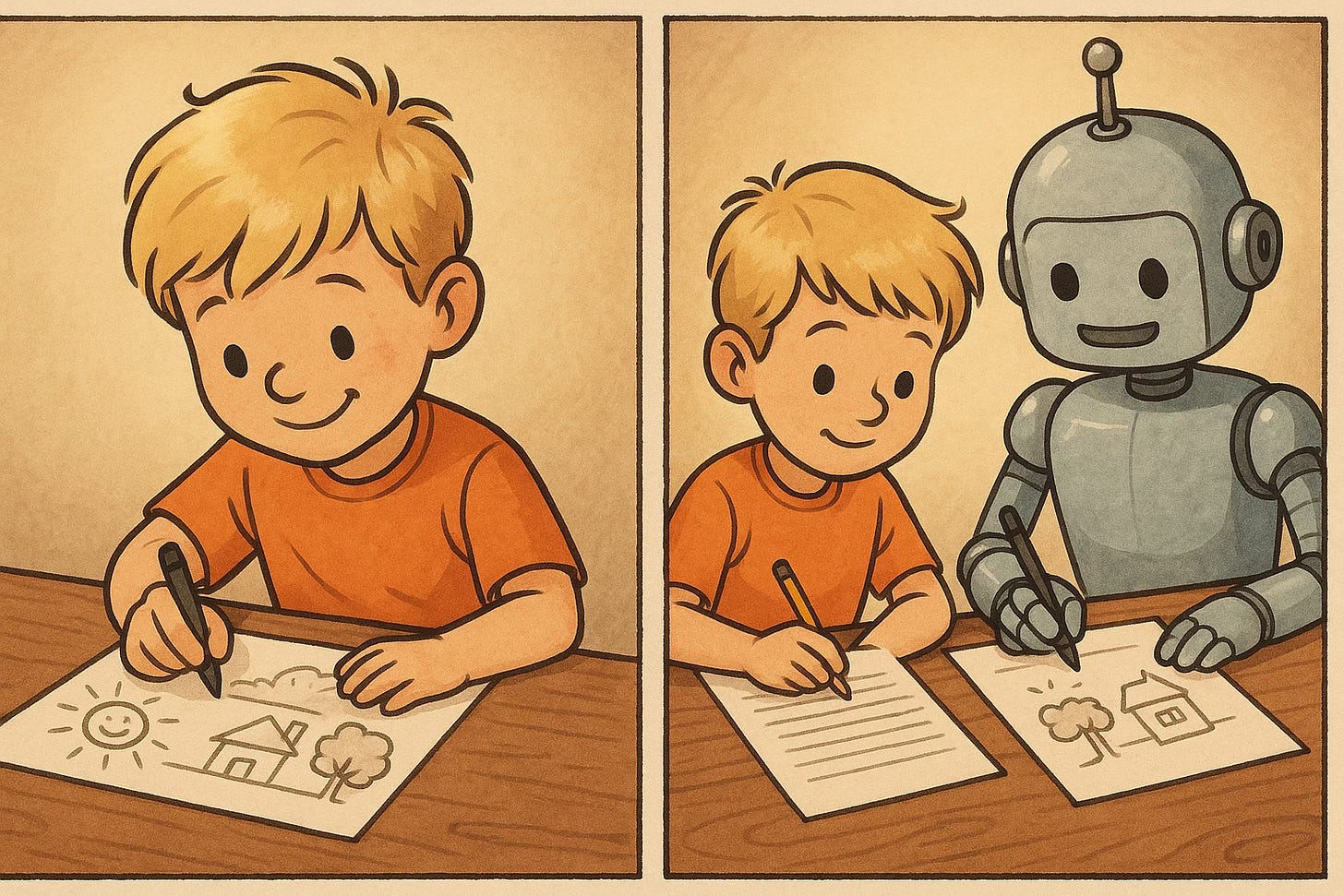

Again, to illustrate the point, an AI-generated comic (unlike Mr Squiggle, my son doesn’t draw upside-down, although I like that the robot is following his lead):

Of course, there are many considerations we would draw on here - what about the role of inclusion and accessibility in the ‘bicycles for your mind’ scenario - but, the key conclusion for me is the following: whatever you are wanting to learn, whatever the goal (riding a bike, drawing a picture, telling a story), the way we scaffold the process and curate how much the learner is able to try, to fall, and then try again, with an expectation of eventual goal achievement, is what always matters.

What we do with a tool like AI when we already have mastery over a skill will always be a completely different experience from someone still acquiring that skill. When I use AI to assist with creative writing and ideation, as a 41-year-old man with a history of published books behind me, I am in a totally different space from my 5-year-old son learning to write and tell his first stories.

I am reminded of that line from Nietzsche:

In the mountains the shortest way is from peak to peak; but for that one must have long legs.

Is this not precisely the scenario we are describing here? For me, I do have long legs, stretched across the years by time filled with walking. I eagerly walk from peak to peak and now I use AI as part of my daily process, whether it be in the creative arts, in my professional work or as a daily walk and talk mentor. But my son - he has little legs. He can’t walk from peak to peak, he needs to learn to climb up the hill, one foot after another. There might be a role here for AI to guide him, to provide accessibility, to ‘ramp’ him up into the climb - but the climb must be his, a result of his own momentum. AI should not carry him up the mountain.

Easy for me to say - I feel like I’m on top of the mountain looking down. But am I really? I have big creative goals I want to achieve still in my life - I want to write a significant book that contributes something good to our human age, something that will take a lot of effort and overcoming, because this is what I value: I value the struggle, the sweat. I’m all about that Beethoven line that he includes in a letter to a friend - “what is difficult is also beautiful, good, great, etc, therefore every person understands that this is the greatest praise that one can give: because the difficult makes one sweat”.

But is this the only way? I’m a man who feels like everything good in his life is because he has overcome himself with great force (being a young boy who stuttered, I overcame this by throwing myself into terrifying situations and creating conditions that I had to rise to the occasion for, I had to harden myself and develop surefire ways to not stutter), but I know this colours my perception too much. The gentle, inclusive side of me wants to make things easy for others, to provide gentle sloping pathways that guide any learning experience towards completion through harmonious means. This is something I feel technology can do so well - so why would I shy away from it?

My son is still drawing every night. We play with AI and technology to make things - we 3D print, we make our movies, we experiment with new AI tools as they come about. My son tells his stories; he’s getting better all the time. He’s only five. His legs are still little. My legs are long, and as time goes on, the longer I sit at my desk, my knees get sore. Bike riding helps. It’s gentle on the joints. I ride, my son rides. As long as we navigate these pathways together, thoughtfully, I have a feeling we’ll be alright.

Addendum: Communication and AI

The other week, I hosted a conversation at Apple headquarters in Sydney with the developer and director of learning design at AssistiveWare, who created Proloquo. You can watch a recording of the conversation below.

The main point I want to draw attention to here is a part of our conversation (at around 29 minutes into the recording) where artificial intelligence and AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication) are discussed. David and Erin make many excellent points on this, particularly the idea that language and communication come about through the same forces discussed above: through trying, through failing, through learning, and through trying again.

If AI is embedded deep in tools like AAC, two twin concerns could emerge: one, is whether the user will actually learn the necessary processes involved in the construction of language to be able to do so independently (an echo of the aforementioned discussion of whether mastery involves a ‘fall’ or not, or to what extent); and two, will the words being communicated actually be that of the user, or that of the dominant algorithm driving the construction of language? There is something so raw and unfiltered about ones own sense of humour, ones’s own observations and personality that beams through the choices we make with our language - that’s why sophisticated AAC systems like Proloquo are so important, to allow this to happen. If AI takes the lead on this, who really is communicating?

Compare this consideration, then, to the experience that my colleague Christopher Hills has in hospital a couple of months ago. You can learn about it straight from Chris in the video below:

Chris tells how he needed to communicate his needs to doctors while he was under serious physical duress. Through a clever utilisation of Switch Control, the Notes app on his iPhone, ChatGPT and Apple Intelligence, he was able to get his message across clearly and efficiently in a manner that would have been impossible in previous times.

This is an example of the value of AI in the communication process, but it’s also perhaps a story about someone who has ‘long legs’ to walk between mountains, to build on our quote from above, perhaps from two vantage points: Chris not only has mastery over the language he wants to construct (and so, he doesn’t need to learn the rules of language), and he has such profound mastery over the technology he uses, that the use of AI as part of his communication paradigm makes perfect sense: this is a bicycle for the mind in the purest sense, it is providing Chris exactly what he needed, the capacity to travel further with his goal (communication) through technology.

These are two different standpoints on the emerging integration of AI into something as fundamental as communication that demonstrate what can be gained, and what can be missed, based on whether we are acquiring mastery or whether we’re already there.

Neuroalethia.

A sensory experience all of your own.

The author Ben Lerner gave an interesting lecture last year at Boston College that he titled 'Erring Together'. In it, he refers to the work of literary critic Rei Terada and her book 'Looking Away'. Terada explores an idea she terms 'phenomenophilia' - in its most basic form, it describes the idea that there are sensory experiences we can have that are impossible to communicate to others.

When you close your eyes you might see little collages of inverted geometries floating across your vision; when you squint, you might see weird light effects that dance against the coloured shadow on a wall; you might find yourself turning your head in just such a way so the sound of a passing train creates a rhythm out of wind gliding across long grass. These are phenomenophilic experiences; they are something you experience without any pressure or obligation (and arguably, no possibility) to share them with anybody else.

This runs counter to many sensory, or even broadly existential, experiences that we have across a day - for the philosopher Immanuel Kant, our aesthetic judgements are something we want to share with others, we want others to agree with. When we find something beautiful, we think others ought to find it beautiful too. We have a 'common sense' that is social at its core.

Lines in the sand.

This consideration of Terada's 'phenomenophilia' brings to mind some thoughts I have on occasion regarding neurodiversity and neurodivergence, and ways in which I feel I diverge from some of the narratives in that space, even if only temporarily. I was, and still am, impressed with the idea of neurodiversity when it emerged - its twin ideals, not only that everybody alive has a mind that is unique to them, but too this is what a healthy society should affirm: the greater the variety of minds in any given room, the more creatively rich that space will be, like the flourishing of ecosystems that contain an abundance of flora, of biodiversity.

When the neurodivergent definition came into use, it made sense: the risk of the linguistics of neurodiversity was that it was too all-encompassing, it played into the 'everybody is a bit on the spectrum' mode of interpreting variance. So, neurodiversity transfigured into less of a description of any individual or group of individuals and rather more into its social ideal. At the same time, neurodivergence provided an opportunity to highlight genuine statistical differences of neurology, it fought back against a potential erasure of care, of need. Not least on an economic front, where definitions delineate diagnostic categories that provide necessary medical and lifestyle support.

One of the challenges I have in this space, however, is the line in the sand between perceptions of diversity and divergence. A quick online image search will show that there is only moderate agreement in terms of what ‘neurodiversity’ even really represents - is it really everybody in a society, or is it a spectrum of non-normative neurotypes: not only for typically associated neurodivergent neurotypes like autism and ADHD, but also for gifted and talented students, for those with dyslexia, with trauma, cultural diversities… to which I feel a desire to say ‘No, that isn’t what neurodiversity represents - neurodiversity is everybody, it is the social idea of everybody in a society having a unique mind. If you want to draw lines in the sand between mental experiences, this is where the neurodivergent framework comes in.’

But then, because the very nature of neurodivergence is focused on those with needs that fall outside the apparent normative statistical average (whether because of medical or social model impacts, universal design, accessibility factors and so on), there is a reliance upon not only specific, characteristic based categories of need (commucation, interaction, executive functioning, all the rest), but also of a shared, social, ‘common sense’ observation of these associated traits.

Community and beyond.

This is readily apparent in just how much social media has played a role in connecting folks within the neurodivergent community, and explaining core lived experiences to those who aren’t. The rise of ‘neurospicy’, the autism and ADHD memes - it’s all about a shared language that says ‘You aren’t alone, others feel this way too’. Not only the neurodivergent community: the LGBTQ+ community, I remember being on Tumblr during the early days and learning about more forms of sexuality and gender identity than I had ever been aware of. Then the neuroqueer communities, the communities of folks exploring their plurality and their multiple headmates and monoconsciousness, and a world of myriad ways of experiencing the world that are expansive and necessary. These are shared spaces where communities flourish around ways of feeling human that can otherwise feel devastatingly isolated.

Circling back on the idea I started with, of Terada’s concept of ‘phenomenophilia’, of sensory experiences that are unique to an individual without any associated responsibility to communicate those experiences to others, I am drawn, at times, to a particular inversion of community and sharing. It doesn’t come from wanting to encourage isolation; anything but. It comes as a way of wanting to frame a sort of mega-amplification of inclusion that provides relief from needing to explicate a state of neurodiversity or a lived experience of neurodivergence. It isn’t post-disability; it is a way of providing a linguistic space for an uncategorised mind. If anything, it is decidedly post-meme.

Neuroaletheia.

Noun. Neu-ro-a-LEE-thee-uh.

The internal act of recognising and accepting the unique experience of one’s own mind, independent of external disclosure or comprehension.

A personal unconcealment: the mind’s unveiling to itself, without necessity or expectation of sharing with others. A relief from commonality.

An ethical stance, recognising the sovereign truth of every mind and calling upon others to honour mental experience without imposing frameworks of interpretation, definition, or external expectation.

Etymology: from Greek neuro- (mind) and aletheia (truth, unconcealment); a private experience of mind and a social ethics of respecting the unseen.

There remains a strong emphasis on communication, translation, and making oneself understood within or alongside a collective within the linguistics of neurodivergence. Not only neurodivergence, but of all aspects of humanity, particularly online - I’m in so many online forums dedicated to the 1990s: all those video games and movies you thought nobody else had played or seen; those brown paper bags with a coin taped on that you took to the primary school canteen for a sausage roll at lunchtime; the feeling of being outside of an evening on your bike with mates in some period of infinite Summer. I am profoundly touched by these shared experiences and love to experience them with a community of others. However, at times I do seek a counterbalance.

This counterbalance is within the domain of feelings, memories, and experiences that I alone feel like I have had. They don’t seem to (yet, on my screen) exist in meme form: they are private moments that, even if they have been experienced by a million others, I certainly don’t know about it. They are my phenomenophilic experiences, and their importance is not whether anyone else has experienced them (I’m not actively seeking the novelty of being the only one to have felt or thought about any particular thing) but rather as a relief from needing to turn the experience into a social act. It can remain mine in the quietude of an unshared self. (Side note: in the midst of a loneliness epidemic, I wonder at times if, paradoxically, one antidote is to have more experiences that are privately yours, for which there is not a social responsibility, a communal expectation, to give or take).

Relief from communicability.

In Lerner’s interpretation of Terada’s explication of phenomenophilia, “the appeal is that no one can be imagined to share [these unique sensory experiences], no one can be imagined to appropriate, benefit from or push one to endorse them. They offer a glimpse not of spontaneous accord, but of a freedom from the demand for agreement”.

Further, to quote Lerner - “instead of anger, or the infinite loneliness of solipsism, for Terada and her phenomenophiliacs there is relief - however soft, mild, fleeting - in the incommunicability of these little perceptual experiences, their asocial moment, precisely because they suspend the pressure of a common sense”. There is no need to convince anybody of your experience. There is no responsibility to a community.

A friend (another in a long sequence of friends) recently received their ADHD diagnosis, and their first comment to me, afterwards, was “I don’t agree with it”. Discussed further, the idea wasn’t that there weren’t traits associated with ADHD that they disagreed with - executive functioning, social - it was that it didn’t represent the delicate, evolving complexity of who they have been, who they are and who they are becoming. Not that the weight of diagnosis needs to capture the entirety of an individual, but it can definitely feel like that way: post-diagnosis, the mind is sometimes perceived as a different entity. The autistic brain, the ADHD brain, the AuDHD brain, etc - it is not the same as just having a brain with a unique sense of humour, a brain that enjoys certain pleasures and avoids certain pathways: it is now a neurodivergent brain, statistically, socially different, existentially and phenomenologically non-normative. And it is now part of a community.

More love.

If the intention here was simply an impetus to radical self-definition, that would be enough for me; to find a social function within this seems secondary, and yet this is also what made neurodiversity such an important idea - the social responsibility it defined in view of biodiversity, that more variance is healthier, better.

What would it look like if we treated students as bearers of internal truths that did not have to be externally explained, shared, or validated to be respected? This is closely aligned with self-diagnosis, for sure - but, it is critically beyond self-diagnosis. Beyond the need for self-diagnosis. Beyond the potential for self-diagnosis. A state of neuroalethia as not rooted in a disability framework but simply a human framework, a phenomenology of being alive. A radical acceptance of nature beyond a shareable linguistics, beyond categorisation.

Neurodiversity and neurodivergence both emerged from a disability paradigm. The intention was to develop a kind, inclusive world view that embraced difference and empowered society to recognise that universal design could provide access and dignity for everybody. I feel though, at times, that something is lost when the lens is positioned only within the language of disability: even when explicit attempts are made to overcome this, I find that rarely moves away from a deficit model. Of course, this is all functional, this is serious territory: there are how many students in school today with how many needs not being addressed, to say nothing of the life beyond the classroom. Again, the goal is not erasure or minimisation. It is about more love.

If you’ve met one person.

This is where a concept of neuroalethia beckons a way of creating an ontology out of the epistemology of neurodiversity: rather than situating our understanding of human variance within a framework of social inclusion, it is trying to position the starting point of the discussion at the front door of the absolute uniqueness of what it is to be you. Not in relation to support needs, but in relation to the private experience of being you that should be provided for and cared for as a universal duty because you are human. And, because we are taking phenomenophilia as our starting point, this is all without an expectation of you ever being able to share this insight of self with others.

A conception of you not as necessarily embodying the shared lived experiences of autistic and ADHD modes of common recognition, but as a quiet soul who enjoys mid-20th century literature and the kindness of strangers; who walks down dry storm water drains and wonders what the balance is between radical kindness and high expectations; who believes love is also about what is not revealed, who meets new people and imagines what they'd look like as skeletons; who writes poetry like his father, who likes to make sure they are certain about being right before they speak in a crowded room just like his son; who has a very particular personality, a very particular body, a very particular conception of time. Where is this dialogue in professional development sessions about neurodiversity? How is this captured in the social commons of neurodivergent lived experience, beyond the commons?

For me, this is a critical understanding of what it is to be uniquely human in a way that really acknowledges it. You could be tempted to say that this is a counterpoint to neurodivergent diagnosis and self-diagnosis because it speaks to a space beyond the potential for diagnosis. But again, the point isn't post-disability, or post-label: it is about pre-disability, pre-label. It is about a ground-floor assertion that the person you meet is someone you have never met before.

None of these thoughts are intended to diminish the reality of neurodivergent advocacy, community, or the importance of diagnosis and support. It is a meditation on what it might mean to cherish the mind’s irreducible individuality alongside our work for collective understanding and inclusion. The chestnut about 'If you've met one autistic person, you've met one autistic person' becomes less impactful the moment you start fitting the model of an autistic mind into a template, a repeatable schema: what if we really held true to that assertion - 'If you've met one person, you've met one person’, and the kindest thing you can do is to believe it.

I’ll finish by linking to an essay I wrote the month that is too long, and perhaps a little out of place, to sit here: it is called “Landscape Within Landscape: Thought as Topography and Topology”. You can read it here:

It feels like an important consolidation of a range of ideas in recent years that I have had with regards to the ‘feeling’ of thought, the link between human subjectivity and the landscapes of nature and urban sprawl, and the central role of analogy in all of this. I reference many of the bright lights who influence me in this space - Gerald Murnane, Douglas Hofstadter, Hermann Hesse. I hope, if you choose to read it, that you find resonance with how your own thoughts feel, beyond the linguistic stream.

If you’ve made it this far through, thank you - warmest regards, and I’ll see you in the next edition of The Universal Sandpit Quarterly.

Craig.